Exo: Testing Scaffold-Based Agent Optimization on GAIA

Testing context-based optimization for agent continual learning. Pareto-optimal cost-performance, a humbling lesson in overfitting, and what I’d try next.

TL;DR

Continual learning — agents that improve from experience — keeps surfacing as a key capability gap. Weight updates are prohibitive at scale; context-based learning is the lightweight alternative. I built Exo to test whether context-based optimization could close the gap between economy and frontier models on GAIA . The architecture: modular ReAct (reflection → domain routing → specialized action) with an adapted GEPA optimizer for trajectory-level self-improvement. Along the way, Grok 4 Fast + my tooling achieved Pareto-optimal cost-performance — higher accuracy than o4-mini + HAL at 4x lower cost. The optimization results were humbling. Validation scores improved steadily over thousands of rollouts. Then I ran the full 300-task test set: the optimized agent scored 3 points worse than baseline. The optimizer had been overfitting the whole time. Core problem: coverage. Context-based optimization needs training signal that covers your test distribution. GAIA spans web browsing, computer use, multimodal tasks, endless edge cases. Because this is a side project, I tried to hack together a training set by splitting GAIA’s validation set. I suspect my data was too sparse and jagged to optimize on properly. Modular architecture showed modest gains (+0.7%); the optimization framework needs a narrower target or much more data.

Code here

What I Built

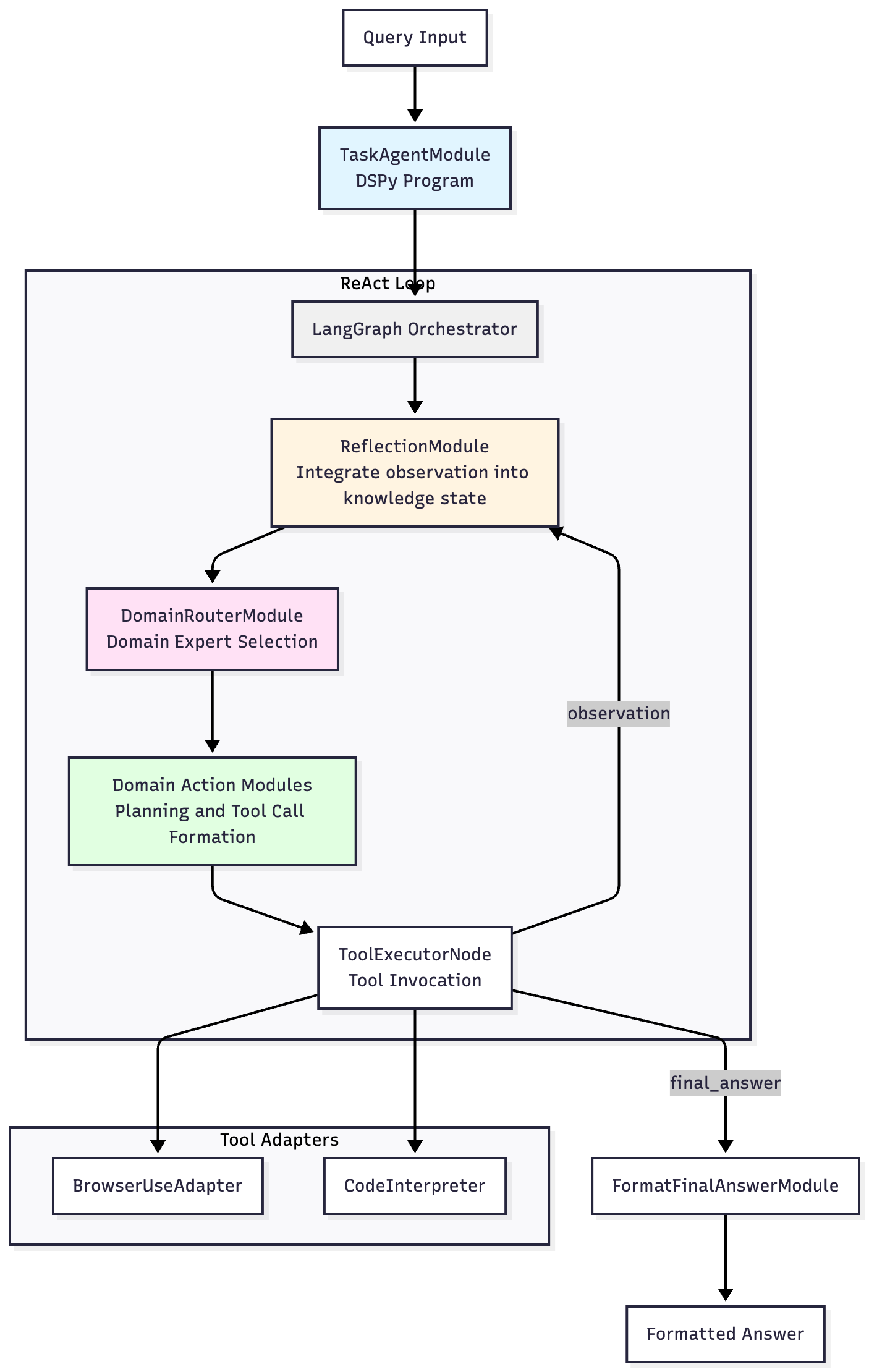

Modular ReAct Architecture (Exo) Decomposed monolithic ReAct into explicit modules operating on a shared trajectory:

- Reflection → Domain Router → Domain Specialist (Action) → Tool Execution → (Repeat)

Five domain specialists: Browser, Wikipedia, ArXiv, Code, Miscellaneous

Key design choice: Unlike subagent architectures where specialists maintain separate contexts, Exo’s modules operate on a single continuous trajectory. Each step routes to the appropriate specialist, but context accumulates without fragmentation. (This addresses context discontinuity problems I observed in earlier subagent-as-tools experiments.)

Trajectory-Level GEPA Adaptation

GEPA provides a useful framework for optimizing LLM prompts, but out-of-the-box it is suitable for “single-shot” LLM applications only. Agents need trajectory-level analysis — you can’t attribute a final failure to a specific step without examining the full chain. I adapted GEPA to:

- Analyze compressed full trajectories to identify key failure point for each trajectory

- Generate improvement feedback to address the failure and score estimated impact for the improvement, for each trajectory

- Use aggregated estimated impact to select the module to target

- Synthesize relevant feedback across trajectories to improve instructions for the target module

Infrastructure & Tooling

Agent benchmarks like GAIA require reliable, efficient tooling. Raw browser HTML is noisy; API rate limits and failures need handling; code execution needs isolation. I built tooling to address these:

- Multi-threaded concurrency in containerized deployment: Tasks are run in parallel, each with its own thread, agent, browser, and code executor. I chose multi-thread concurrency for maximum compatibility and reuse with DSPy’s Evaluator and Optimizer. The application is Docker containerized for easy, portable, and reliable deployment.

- Interactive browser use with markdown content extraction: Integrated browser-use tools for use in my agent, with per-thread browser isolation to work with DSPy’s multithread Evaluator. Added webpage content extraction with conversion to clean markdown. Reduces token count vs raw HTML while preserving structure the model needs.

- Wikipedia API wrapper: Direct structured access to content and revisions via the MediaWiki API. Faster and more reliable than browser-based Wikipedia access; returns clean text without navigation chrome.

- ArXiv search: API-based paper search and abstract retrieval. Avoids browser overhead for a common GAIA task type.

- Python code execution: GAIA has a long tail of tasks including opening Excel, Powerpoint, Biopython, and other files, data analysis, etc. Python provides an escape hatch for low frequency or unanticipated tasks as an “everything tool”.

- Multimodal tool wrappers: Decouples vision model from reasoning model. A distilled representation of the agent’s context is passed into the tool, providing valuable implicit information to the vision model as it describes the target image, browser screenshot, audio, or PDF.

- MLflow experiment tracking: Structured logging of trajectories, scores, and instruction versions across thousands of rollouts. Made it possible to debug optimization failures and compare runs systematically. Provides data for future finetuning or context-based learning.

This tooling — independent of the modular architecture — is what shows up in the cost efficiency results below. A vanilla ReAct scaffold with good tools can be Pareto-competitive.

The Hypothesis

Claim: Modular decomposition + automated trajectory-level optimization should outperform monolithic ReAct.

Reasoning:

- Monolithic prompts for diverse tasks get bloated; attention degrades

- Long trajectories with noisy observations stretch context; distilled structured outputs should help

- Manual agent optimization doesn’t scale; automated optimization should compound

- Domain specialization should improve per-domain performance without subagent fragmentation

What I Tried First

Before settling on this architecture, I experimented with subagents-as-tools - giving a top-level agent tools to spawn specialist agents for browsing, coding, etc. Problem: the interface between the agent and subagent became a point of context loss, dependent on the ability of both agents to communicate flawlessly. Additionally, complex tasks, like those found in GAIA, often require discovery, further complicating the transmission of context, since what information each agent needs to pass to the other is not obvious.

This motivated the “single trajectory, multiple specialists” design — preserve continuity while still enabling domain-specific prompting.

The Experiment

I used the GAIA validation set to create a new train-validation split and ran my modified dspy-GEPA optimizer on my Exo modular ReAct agent for thousands of rollouts. Important context: the GEPA algorithm validates updates—all updates are created from train set trajectory feedback, but must improve validation set scores for the update to be accepted. The GEPA author recommends using the smallest validation set that accurately represents the problem domain to reduce compute and training time. I used a small validation set — 5 items — but resampled the 5 items from the held-out validation set regularly to balance training efficiency with overfitting risk.

Curriculum

GAIA splits tasks into 3 difficulty levels, and I tagged each task with the tool group it required (e.g., web browsing, wikipedia, calculator, etc.). From this, I built a curriculum, starting with the easiest tasks that required the most commonly required tool group: web browsing. After validation scores started to plateau, I moved onto the next tool group, progressively expanding to all tool groups, then progressed the difficulty.

Apparent Progress

Over tens of runs and thousands of rollouts, I saw validation score generally improve. On some runs, performance was already strong (80%+), and on others, scores did not improve. After a while, I decided it was time to stop optimizing and start evaluating.

Test

I tested 2 versions of my agent, Exo, and 1 baseline (Vanilla ReAct), on the full 300 task GAIA test set. The baseline, Vanilla ReAct, is DSPy’s implementation of ReAct, with the Exo tool set. The two versions of my agent were (1) an unoptimized version, to test the effect of the modular architecture without GEPA optimization and (2) a distilled version of the GEPA-optimized agent. The GEPA-optimized version is distilled because on preliminary validation set evaluations, the non-distilled version performed worse than both the unoptimized version and the baseline. After reviewing the GEPA-generated instructions and finding them problematic, I attempted to salvage them by having Claude remove redundant and incoherent information, and then I deleted obviously wrong guidance. The distillation partly invalidates that variant’s results but re-running the optimization was out of scope for this experiment, and an optimistic preview of potential performance seemed more informative than verifying its underperformance.

Results

Test set performance (using Grok 4 Fast, a top performing economy model, at $0.20/$0.50 per million tokens):

| Variant | Accuracy | Error Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Vanilla ReAct baseline | 54.8% | 1.7% |

| Exo (unoptimized) | 55.5% | 5.6% |

| Exo (GEPA-optimized, distilled) | 52.5% | 3.7% |

What the numbers show:

- Modular architecture: +0.7% accuracy, but +3.9% higher error rate from unresolved scaffold issues

- GEPA optimization: hurt performance by 3 points despite validation safeguards

- Errors concentrated in addressable edge case handling — suggesting potential accuracy gain of up to 3.7% over baseline from unoptimized modular architecture

GEPA-generated instructions

GEPA generated very long instructions: up to 2.2k tokens in one module, with detailed guidance relating to specific tasks in some cases, and incorrect guidance in others.

Cost Efficiency

Scaffolds often focus on architecture, but tooling quality matters just as much. Most ReAct implementations share similar reasoning loops—what differs is the tools: how reliably they extract content, handle edge cases, and return usable observations.

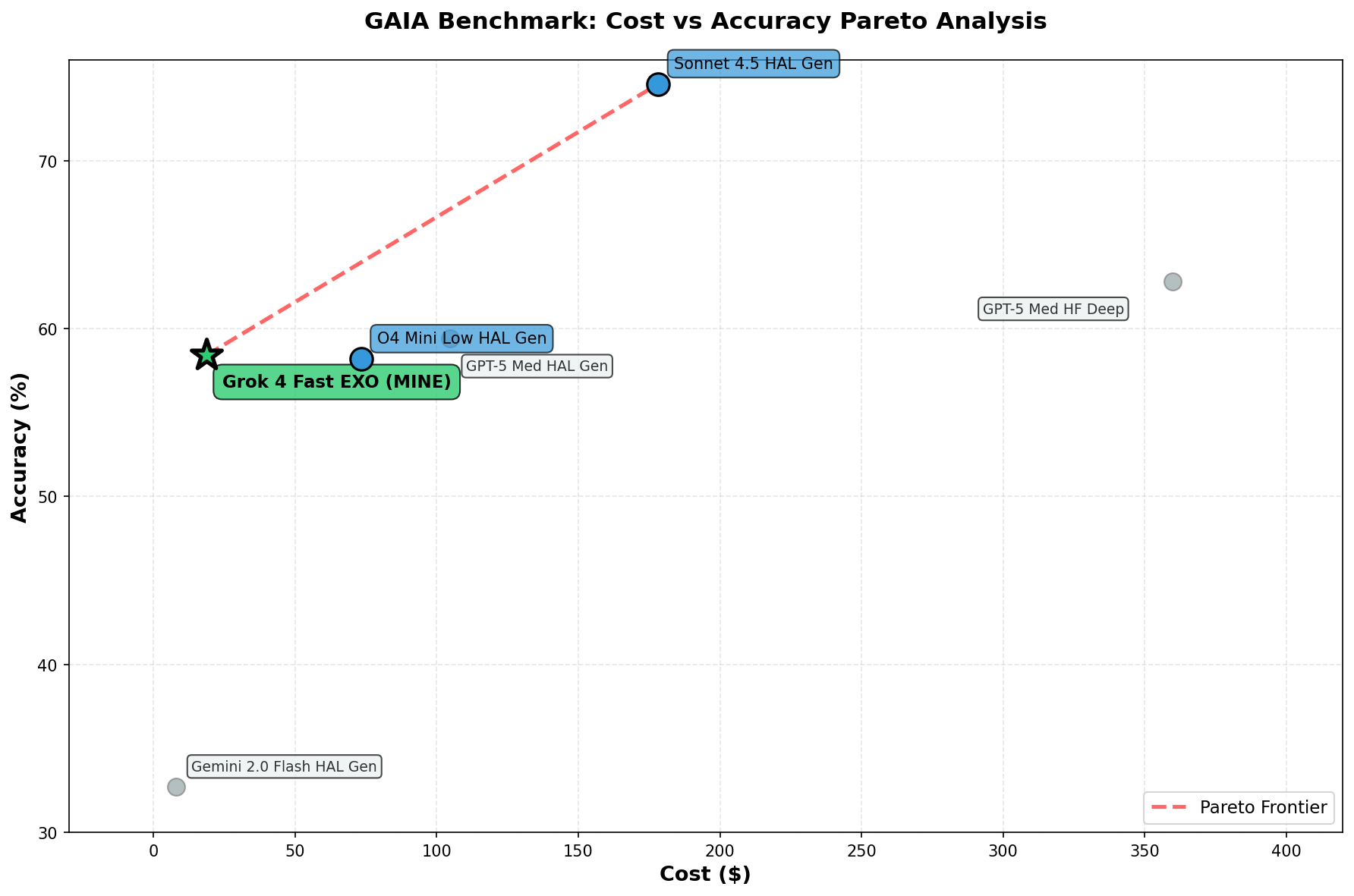

Here’s how my vanilla ReAct baseline compared to HAL entries on the GAIA validation set :

| Setup | Accuracy | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Sonnet 4.5 + HAL | 74.6% | $178.20 |

| GPT-5 Medium + Open Deep Research | 62.8% | $359.83 |

| GPT-5 Medium + HAL | 59.4% | $104.75 |

| Grok 4 Fast + Exo tooling | 58.4% | $18.62 |

| o4-mini-low + HAL | 58.2% | $73.26 |

| Gemini 2.0 Flash + HAL | 32.7% | $7.80 |

Please note that all the provided comparison points (except for GPT-5) are Pareto-optimal on HAL’s leaderboard.

The combination of Grok 4 Fast and my tooling (browser-use integration with markdown extraction, Wikipedia API, ArXiv search, containerized code execution) produced a new Pareto-optimal result — higher accuracy than o4-mini + HAL at ~4x lower cost.

I can’t cleanly attribute how much comes from Grok 4 Fast’s pricing versus my tool implementations. But the result suggests both matter: a well-priced model with well-engineered tooling can compete on cost-performance even without architectural innovations. The modular architecture and optimization framework are where I see unrealized potential; the tooling already works.

Secondary Results

I tested whether modular decomposition helps older models more than newer ones (before labs focused heavily on agentic capabilities).

Scores on 50-task validation set sample, using DeepSeek V3 0324:

- Vanilla ReAct: 30% accuracy

- Exo unoptimized: 32%

- Modest gains persist across model tiers

Reflections

Context-Based Optimization Is Under-Explored

Weight-based learning has gradient descent: a mature methodology for synthesizing large numbers of examples into generalizable parameter updates. Context-based optimization has no equivalent. You have to explicitly integrate trajectory feedback into limited context, balancing detail against attention degradation. The research surface here is much less charted.

This isn’t to say context-based approaches are doomed—just that the methodology is younger. Labs working on agent performance throw massive resources at the problem: RL environments, synthetic data pipelines, entire teams. I was one person with an adapted optimizer. The gap between what I could iterate on and what frontier approaches require became clearer over the project.

Why GEPA Optimization Failed

The GEPA-optimized agent underperformed despite GEPA’s built-in validation. Every update must improve held-out validation scores to be accepted. I trusted this mechanism too much.

The microbatch problem: GEPA processes training minibatches (default: 3 tasks), generating feedback and updates based only on current batch trajectories. On a diverse benchmark like GAIA, 3 tasks rarely share enough structure for generalizable improvements. My adaptation could synthesize feedback across trajectories, but I didn’t enforce a minimum — so updates often reflected single-task quirks.

Validation set size: Started with 10-task validation sets, cut to 5 with rotation per GEPA’s guidance (smaller = faster iteration). Still overfitted. Simply increasing the validation set size is one of the easiest changes to try, if I were to continue this experiment.

Instruction bloat: Generated instructions grew to 1-2k tokens per module, with task-specific guidance that hurt generalization. If I were to continue this experiment, I would consider adding mechanisms to constrain length, such as periodic distillation.

What I’d build differently: Accumulate all historical feedback for a module version before proposing updates, rather than just current batch. Consider memory-based approaches (inject learned heuristics at runtime) instead of instruction mutation. ReasoningBank explores this direction.

Benchmark Choice Matters

GAIA spans web browsing, code execution, document analysis, and multimodal reasoning, resulting in a huge surface area. This means sparse signal per domain: it’s hard to isolate what’s working, iteration cycles are expensive, and feedback is noisy.

I probably should have started with a narrower benchmark, or a vertical slice of GAIA — just browser tasks, or just Wikipedia lookups — validated the approach on denser signal, then expanded. GAIA also happens to be a benchmark labs are actively pushing on; my architecture improvements got swamped by model improvements released during development. On the bright side, I suppose this means I chose a good domain to work on.

In retrospect, this v1 was scoped too broadly for the constraints (one person, side project, limited compute). The infrastructure and methodology are reusable; the benchmark choice made iteration harder than necessary.

What Worked

Tooling. The custom tools—browser-to-markdown extraction, Wikipedia API, ArXiv search, containerized code execution — combined with Grok 4 Fast to produce a Pareto-competitive result. This holds independent of architecture choices; a vanilla ReAct scaffold with good tools is enough to compete on cost-performance.

Modular architecture. Consistent (if modest) gains across model tiers: +0.7% on test with Grok 4 Fast, +2% with DeepSeek V3. Domain specialists operating on shared trajectory avoid the context fragmentation of subagent approaches. Small but directionally correct.

Infrastructure. Docker container running LangGraph to orchestrate DSPy modules, with multi-threaded eval and MLflow tracking. Tested and reusable for future agent work.

Optimization framework. The GEPA adaptation didn’t produce better agents in this experiment, but the methodology — trajectory-level analysis, module-targeted feedback, validation-gated updates — is promising.

What I’d Try Next

Narrower domain first. Validate on a single vertical (web browsing or code), then expand. Denser feedback, cheaper iteration, cleaner signal.

Smaller architectural increments. Add reflection module, measure. Add routing, measure. I made too many bets simultaneously.

GEPA rebuild:

- Historical feedback accumulation (all trajectories for a module version, not just current batch)

- Explicit instruction length budget with periodic distillation

- Larger validation sets (20+) or synthetic task augmentation

- Memory-based updates: inject learned heuristics at runtime rather than bloating base prompts

Different benchmark. Something narrower, less actively targeted by labs, where scaffold improvements can be isolated from model improvements.

Final Thoughts

Continual learning keeps surfacing as a key capability gap — Sutton argues LLMs are a dead end without it, Ilya frames it as the next frontier. Sutton’s take strikes me as overly pessimistic. As an engineer, I don’t see a fundamental blocker — just problems to work on. Context-based learning is the obvious lightweight approach to try: weight updates are prohibitive at scale, and we already know in-context learning works.

My bet: context-based learning has a place in the toolbox alongside SFT and RL. Maybe as a bridge between weight updates — an agent learns in-context until it can complete a task, then successful trajectories feed back into finetuning.

Exo implements a form of continual learning — the agent learns from past trajectories, in context, to improve on future tasks. My results don’t prove context-based optimization works or doesn’t — they just show GAIA was the wrong target at side-project scale.

Six months ago I’d never built an agent. I started from smol agents and Open Deep Research, tried Atom of Thought, experimented with sub-agent-as-tool architectures, and landed on shared-trajectory modular ReAct. I didn’t nail the results I wanted, but I built infrastructure that works, tested ideas, and have hypotheses for what to try next.

Technical Appendix

Basic architecture

Exo leans heavily on DSPy modules for evaluation, optimization, and LM interactions. It uses LangGraph for control flow structure. The agent is wrapped in a DSPy program to enable DSPy optimization, with LangGraph orchestrating flow between DSPy modules.

Exo leans heavily on DSPy modules for evaluation, optimization, and LM interactions. It uses LangGraph for control flow structure. The agent is wrapped in a DSPy program to enable DSPy optimization, with LangGraph orchestrating flow between DSPy modules.

Module Signatures & Reflection

The agent’s core reasoning is structured through DSPy signatures that define input-output contracts for each module. The ReflectionStepSignature serves as the agent’s state comprehension layer, taking the latest observation and producing:

- observation_summary: Evaluation of the last action’s success/failure

- facts/constraints/open_questions/assumptions: Evolving knowledge state

- procedural_memory_update: Actionable insights for future tasks

This reflection output feeds into DomainRouteSignature (selecting tool domains) and ActionSignature (planning and executing tool calls). ActionSignature elicits strategic reasoning (working_plan, action_justification) in addition to a tool call (function_name, arguments).

Agent Graph Architecture

The ReAct agent (react_agent.py) implements a reflection → router → action → tool_executor cycle in LangGraph. Each task gets an isolated ReActAgent instance with dedicated browser and code interpreter resources. The agent maintains structured history through HistoryItem records containing observation summaries, route selections, and action descriptions from complete cycles only. After the ReAct agent completes its task, its final answer is passed through an optimized FormatFinalAnswerModule for formatting, since GAIA grading is based on semi-exact match.

TaskAgentModule (task_agent_module.py) wraps the ReAct agent graph and final answer formatting as a DSPy module, enabling program level optimization of all DSPy submodules.

GEPA Optimization Adapter

The DspyFullTraceInstructionAdapter extends DSPy’s standard adapter to support full-trajectory reflection. During optimization, FullTraceComponentSelector analyzes complete execution traces using an LLM-based reflector (FullTraceReflectionSignature) that:

- Compares agent trajectories against human solution steps

- Identifies the component (Reflection, Domain Router, Action, etc.) most responsible for divergence

- Generates generalizable feedback targeting that component’s specific role

Component assessments are stored per-iteration in the adapter (a workaround to avoid modifying upstream GEPA) and consumed during instruction proposal generation. The reflector produces estimated_impact scores to prioritize which component to optimize first. Feedback emphasizes general strategies (e.g., “check internal navigation before search fallback”) over task-specific details.

Structured Output Schemas

Pydantic models enforce type safety across the system. ToolCall uses OpenAI-style schema (name + arguments dict), while HistoryItem packages complete cycle information for context passing. The ReActAgentState reducer functions handle list appends and dict merges, with build_complete_history_items ensuring only fully-completed cycles appear in module inputs (preventing partial/corrupted context).

Infrastructure Setup

Browser Isolation: Each agent gets an isolated BrowserUseAdapter with dedicated event loop and Playwright browser context. A threading semaphore limits concurrent browser launches to prevent CDP contention. Cookies load via CDP after startup, with sanity pings catching bad socket states early. The fetch_binary method bypasses captchas using browser cookies, with disk-cached results for efficiency.

Code Sandbox: CodeInterpreterConnection wraps smolagents.LocalPythonExecutor, an artifact from the agent’s evolution from HF smolagents. Execution is wrapped in a thread pool executor with timeout to prevent excessively long-running code from blocking the agent indefinitely. Output truncation provides a safeguard against excessively long outputs overwhelming agent context.

Docker: The deployment is run through docker compose, with connected agent and mlflow services. Tests are run in a separate Docker Compose environment for isolation, with the same image for consistency.

© 2025 Alex Choi.